Palácio do Planalto by Niemeyer

Words Tom OsmondDate 05 July 2019

It’s the architects of the world who both literally and figuratively put cities on the map. It’s the buildings, roads, sidewalks, subways, and squares that facilitate the way humankind interacts with the Earth, and it’s the landmark buildings and their histories that can define a country’s identity and international importance. We’ve picked a handful of architects who did more than their fair share in making their cities what they are—all while defying the odds.

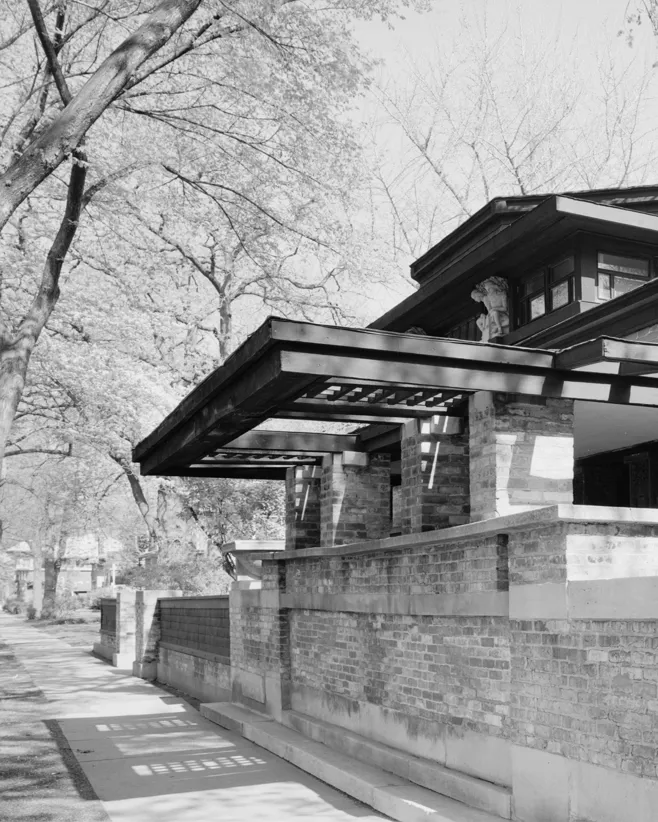

Frank Lloyd Wright

First up, El Alto. It’s almost as though this sky-high Bolivian settlement, after officially becoming a city in 1988, did all it could to break free from its former slum status on the peripheries of La Paz and reincarnate itself as the administrative capital’s more flamboyant neighbor. This can be attributed to Freddy Mamani Silvestre, whose modernist architectural pastiches of native weaving patterns started popping up in the mid-2000s when the country’s first indigenous president, Evo Morales, assumed office. Mamani’s architecture is not only a phantasmagoric ode to his and Morales’ Aymara heritage, but also has the impression of a disco-Baroque-spaceship landing on a different planet—a vivid anti-colonial statement that signposts a historic turning point for indigenous Bolivians.

Images by Peter Granser from El Alto 2016 published by Edition Taube (editiontaube.de)

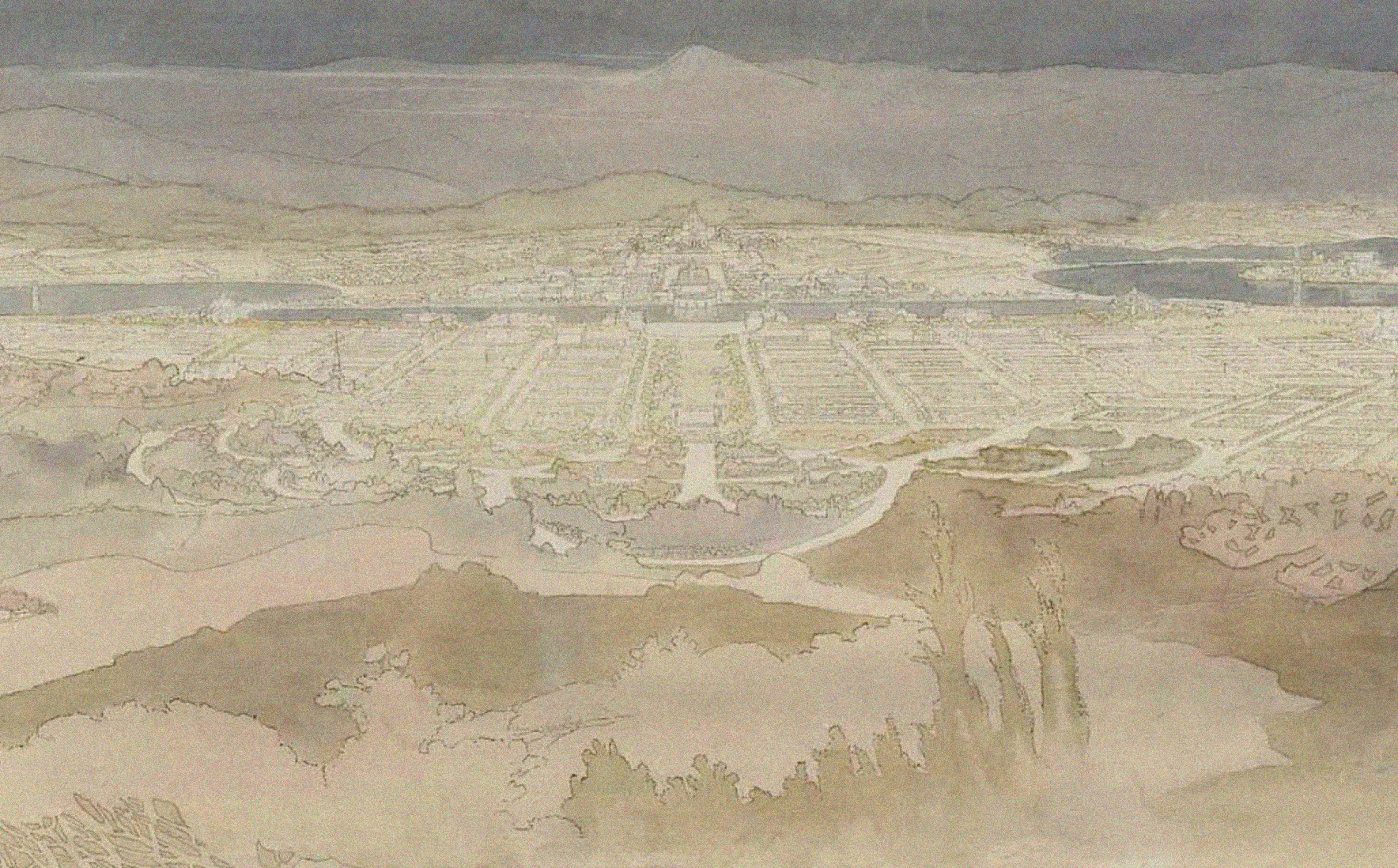

You’ve heard of Frank Lloyd Wright, right? How about his unsung colleague responsible for honing a huge part of Wright’s visual identity and creating some of the best architectural drawings in the U.S. at the time? Marion Mahony Griffin, along with her colleague and husband Walter Burley Griffin, went on to design the Australian capital of Canberra. Walter Griffin was responsible for most of the design, while Marion Griffin’s watercolor renderings were instrumental in wowing the panel of the international Federal Capital Design.

Legend has it that L.A. architect Paul Revere Williams learned to draft renderings upside down, due to his (white) clients not wanting to sit next to an African-American during consultations, preferring instead to sit across a table. As well as circumnavigating the racial prejudice of early 20th-century U.S. with such grace and often being legally barred from cities in which his buildings were erected, Williams became the first African-American member of both the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the AIA College of Fellows (FAIA), as well as being posthumously honored with an AIA Gold Medal in 2017.

Williams is responsible for over 2,000 private homes in L.A., including Frank Sinatra’s “Push-Button House” and the residences of a host of other silver screen names in and around Hollywood, as well as such landmarks as the Theme Building at LAX Airport, Los Angeles County Courthouse, and Westwood Medical Plaza. Williams was also orphaned at the age of four, perhaps explaining his career-long focus on designing homes for families.

La Concha Motel

L.A. airport's Theme Building by Williams image courtesy John Zacherle

Lastly, when the Brazilian capital was moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília in 1960, Oscar Niemeyer was commissioned to design much of the government quarter, including the National Congress of Brazil, the Cathedral of Brasília, and the president’s official residence. Niemeyer was a member of the Brazilian Communist Party, meaning that the U.S.-supported military coup d’état of 1961 sent Niemeyer’s career into precarious existence right at its peak.

Fleeing to Paris after a crackdown on prominent figures on the left, Niemeyer continued to flourish as an architect, building Tripoli’s International Permanent Exhibition Centre, the University of Science and Technology-Houari Boumediene near Algiers, and the French Communist Party headquarters in Paris. After the end of the military regime in 1985, Niemeyer returned to cherry-top his contribution to Brasília’s skyline, most notably with the Panteão da Pátria e da Liberdade Tancredo Neves and the Latin American Memorial.

Brasília by Niemeyer

Oscar Niemeyer